Antibiotic Use for Canine Pyoderma

Many diseases have the potential to predispose dogs to the development of superficial pyoderma. In order to appropriately and successfully use antibiotics in the treatment of canine superficial pyoderma, it is important for veterinarians to be familiar with these potential underlying diseases. This module describes these diseases, as well as sound approaches for judiciously prescribing antimicrobial drugs to treat canine superficial pyoderma, in order to minimize the development of antibiotic resistance.

Learning Outcomes

This submodule aims to introduce appropriate treatment for canine superficial pyoderma, including the judicious use of antibiotics. By the end of the module, you will be able to:

- Discuss how antibiotics are frequently used in the treatment of canine pyoderma.

- List the factors to be considered when choosing antibiotic therapy.

- Identify the underlying causes of canine pyoderma and possible diagnostic and treatment options.

- Describe the importance of bacterial culture and susceptibility testing and effective communication with the client.

- Demonstrate understanding of how animal and human health each may be affected by antibiotic resistance.

- Introduction

- Differential Diagnoses

- Physical Examination

- Diagnostic Tests

- Laboratory Findings

- Initial Treatment

- Choosing an Antibiotic

- Clinical Response to Treatment

- Culture and Susceptibility Testing

- Sensitivity Results and Summary

- Lessons Learned When Treating a Bacterial Skin Infection

- Module Summary (Antibiotics Use for Canine Pyoderma)

- References (Antibiotics Use for Canine Pyoderma)

Introduction

You are a recent graduate from veterinary school and have just started as a new associate in a rural veterinary hospital. You are the only doctor at the clinic today for this mixed animal practice—everyone else is out on farm calls. A long-time client of the practice (for both small and large animals) brings in her family’s resident farm dog, Junior, who is also her kids’ best friend and sleeps with the kids every night. You try to find Junior’s chart but are unsuccessful, as many charts have been misplaced during the clinic’s transition to electronic-based records.

Initial Case Presentation:

Junior is a four-year-old, neutered male Golden Retriever.

History:

Junior presents to your animal hospital with a history of “itching” that has been present for at least the past year-and-a-half, according to his owner Joyce. Recently, the kids have been complaining that Junior’s scratching has been making it difficult for them to fall asleep. On a scale from 1−10 (with 1 being mild pruritus and 10 being severe) Joyce grades Junior’s pruritus as a 7. The pruritus is year-round (nonseasonal), and since the kids started complaining Joyce has noticed that Junior has scabs and bumps on his skin. This was Joyce’s main concern today.

Differential Diagnoses

Based upon the history provided by Junior’s owner, you believe that the bumps and scabs are signs of a secondary superficial pyoderma, and you begin to formulate a list of differential diagnoses in your mind that could predispose a dog to develop superficial pyoderma.

What can predispose a dog to develop superficial pyoderma?

Several diseases/disorders can predispose animals to developing superficial pyoderma. This predisposition is often due to conditions that impair defense mechanisms of the skin. The skin has innate defense mechanisms which help defend against chemical, physical and microbial insults. Some examples of these defense mechanisms include the stratum corneum, cells that resemble a brick wall; fatty acids that have a bacteriostatic effect; defensins, which are small antimicrobial peptides; and resident bacterial flora, which will compete with the pathogenic flora for space and nutrients. The skin normally defends itself well; therefore, it is smart to always consider a bacterial skin infection secondary until it is proven otherwise

|

|

Why do certain diseases/disorders predispose to infection?

1. Pruritic disorders

When a dog has itchy skin disorders such as allergic or parasitic diseases, scratching, chewing, or biting will mechanically remove the stratum corneum, which is a very important skin barrier. Moreover, the process of chewing can result in skin overgrowth of Staphylococcus pseudintermedius (which lives normally in the mouth, nares, and anal ring of dogs).

2. Hormonal disorders

In Hypothyroidism and hyperadrenocorticism (Cushing’s disease) are not pruritic diseases but are often complicated by secondary skin infections which can become pruritic, the lack of sufficient thyroid hormone, which is very important to maintain the normal metabolism of almost all cells in the body, will result in abnormal function of the skin immune defense. In Cushing’s disease the state of chronic excess cortisol secretion will lead to skin atrophy (the “brick wall” becomes very thin), and to suppression of the normal immune defense.

3. Keratinization disorders

One of the main functions of the skin is to produce keratin and special lipids to form the stratum corneum, which is composed of completely keratinized epithelial cells (also known as corneocytes) and an intercellular lipid lamellae. A brick wall is a perfect analogy for the stratum corneum, where the brick is the corneocyte and the mortar is the lipid lamellae. Moreover, a brick wall is a barrier against the entrance of invaders, just as the stratum corneum is a barrier against microbial, chemical, and physical insults. Keratinization disorders can be primary or secondary and are associated with abnormalities of the stratum corneum. Therefore, animals with keratinization disorders are very prone to develop secondary skin infections. Keratinization disorders are nonpruritic disorders, but pruritus often follows from the secondary infections. Examples of keratinization disorders include acne, canine primary seborrhea, zinc responsive dermatosis, and sebaceous adenitis.

Physical Examination

You perform a thorough physical examination on Junior and find the following:

- Body Condition Score (BCS) = 7/9

- Erythema in inguinal region

- Excoriation on one pinna, but ear canals are clean with mild erythema and intact tympanic membranes

- Pustules, papules, and yellowish crusts on the ventral abdomen (see photo below)

- Epidermal collarettes on the ventral abdomen/flanks with mild alopecia (see photo below)

- Mild interdigital erythema localized to all four feet

- All other body systems are within normal limits

Your physical examination findings suggest that Junior has a superficial pyoderma, as you suspected, which is characterized by the presence of pustules, papules, yellowish crusts, and epidermal collarettes. Combining Junior’s clinical presentation (signs of superficial pyoderma and erythema localized to ventral abdomen, flanks, and paws) and the history provided by his owner, you begin to narrow your mental list of differential diagnoses. You would like to ask Joyce a few more questions in order to narrow in on a possible underlying cause for Junior’s skin condition.

What other questions would you like to ask Joyce?

|

|

Narrowing Your Differential Diagnoses

After speaking with Joyce a little bit longer and asking pertinent questions, what have you narrowed your list of differential diagnoses to? What are the most likely conditions that could have predisposed Junior to develop the secondary superficial pyoderma? Click yes or no for each.

Diagnostic Tests

To help narrow your list of differentials even further, you would like to run some tests. What quick, in-house diagnostic tests would you like to perform while Junior and his owner are at your clinic?

|

|

More Diagnostic Testing

What further diagnostic test(s) would you like to run, if any?

|

|

Laboratory Findings

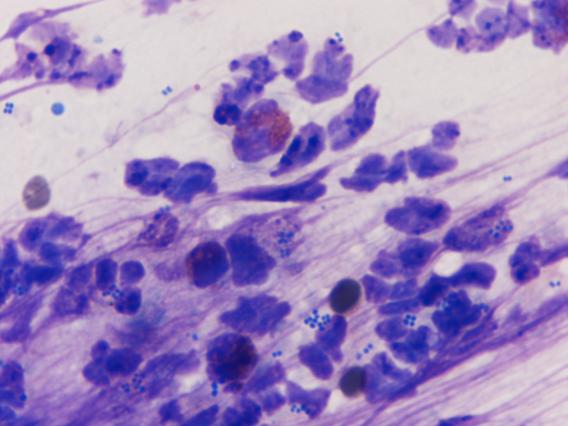

Your in-house tests reveal no mites on skin scraping and a large number of degenerative neutrophils with intracellular cocci on the impression smear (see picture below).

|

|

Other possible findings on skin scraping/impression smear:

|

|

Adult Demodex canis mite |

|

|

Sarcoptic scabie var. canis mite |

|

|

Adult Sarcoptic scabie var. canis mite and egg |

|

|

Malassezia spp. fungi |

|

|

Cheyletiella spp. mite with characteristic hook-arrow |

|

|

Mixed bacteria of rods and cocci |

Diagnosis

Based upon your in-house tests and physical exam findings you confirm your presumptive diagnosis of secondary superficial staphylococcal pyoderma. You explain to Joyce that you found bacteria on the samples that you took from Junior’s skin and that pyoderma is a bacterial infection of the skin. You also explain that pyoderma is usually secondary to an underlying disease, and it is very important to address any underlying conditions, otherwise the pyoderma may never resolve or will frequently recur. You explain that you suspect that the underlying cause of Junior’s pyoderma is likely to be atopic dermatitis (allergies to environmental allergens such as house dust, house dust mites, etc.) or a cutaneous adverse food reaction (a food allergy), given the age at which Junior’s pruritus started and the clinical signs of redness localized to the ears, feet, and inguinal regions. Moreover, Junior’s clinical signs and the lack of contagium and negative skin scrapings, make sarcoptic mange or cheyletiellosis (both also itchy skin disorders) very unlikely.

You then explain to Joyce how you would like to address the most likely causes of Junior’s pyoderma. First, you recommend treating the secondary superficial pyoderma and then starting Junior on a strict food elimination trial. In dogs with year-round signs of allergy, you have to rule out food allergy before investigating atopic dermatitis. Once food allergy is ruled out, you can discuss with the owner the option of having skin and/or serum testing performed to support your presumptive diagnosis of atopic dermatitis, and, more importantly, to select allergens that will compose a vaccine for immunotherapy.

Joyce agrees with your plan, although you suspect that she does not completely understand everything that you have explained. You realize that it may take several appointments and well written discharge instructions to adequately convey the underlying issues that Junior and his family are facing. For now, Joyce is anxious to get home and simply wants a “magic pill” to stop Junior’s itching and heal the bumps and scabs on his skin.

Initial Treatment

Because of Junior’s pyoderma and significant pruritus, you tell Joyce that you would like to start him on some antimicrobial therapy (both topical and oral) because secondary pyoderma typically aggravates the pruritus associated with an allergic condition. You may also consider starting with topical antimicrobial alone for the first two weeks, prior to starting oral antibiotic, as some cases of more localized or less severe pyoderma will respond to topical therapy alone. Topical antimicrobial options include chlorhexidine-based shampoos for weekly baths and chlorhexidine spray or mousses for daily use on affected skin areas.

|

|

Choosing an Antibiotic

In order for an antibiotic to be effective at killing the bacteria present, it needs to reach adequate concentrations in the body organ of interest after oral dosing. Moreover, the antibiotic has to be efficacious against the organisms causing the infection and safe for the patient. The table below provides examples of some antibiotics that are good empiric choices for treating staphylococcal skin infections in dogs. You should remember two important things:

- The most common bacterium that causes skin infection in dogs is Staphylococcus pseudintermedius, and most strains of this bacterium produce β-lactamase, which will inhibit the efficacy of many β-lactam antibiotics.

- The antibiotics that cannot be used empirically to treat a staphylococcus infection include: penicillins, ampicillin, and amoxicillin, which are all β-lactam antibiotics. Some synthetic potentiated penicillins (e.g., amoxicillin-clavulanic acid) and cephalosporins are β-lactamase resistant and may be used to treat infections empirically. In addition, you should not use tetracycline or streptomycin to empirically treat staphylococcus infections because most strains will be resistant to them.

The length of treatment of any episode of infection is also important to consider. Not treating an infection for an adequate period of time will result in nonresolution (despite possible clinical improvement) or frequent recurrence (or what may appear to be true recurrence but is actually nonresolution of initial infection). The rule of thumb regarding the treatment duration of superficial pyoderma is to treat each infection episode for seven days beyond the resolution of clinical signs. Total treatment duration may take up to six weeks. If Junior has been treated previously with antibiotics for this condition and the skin lesions never completely resolved, it is possible that the duration of treatment was inadequate or the bacteria may have developed resistance. The length of treatment may also affect owner compliance—you must emphasize to your client the importance of administering the antibiotic strictly as directed and completing antibiotic therapy as prescribed until the recheck appointment.

Although rare, adverse effects of antibiotic therapy can occur. Most oral antibiotics will cause nausea and sometimes vomiting and diarrhea. Owners should be aware of these potential side effects and should notify you if one or more occur. Clearly explain to the owner any possible side effects that may occur due to the medication you prescribe and possible ways to lessen these effects (e.g., for some antibiotics giving them with food or probiotics may help).

As mentioned above, with pyoderma it is very important that you recheck the patient to ensure that the skin lesions have completely resolved. This reexamination will help you decide whether or not you are going to perform a culture and susceptibility test at this subsequent visit. For example, if Junior had received antibiotic therapy multiple times in the past and the correct dose was used, you should perform culture and susceptibility testing.

You explain to the owner that you will need to recheck Junior in two to three weeks. Let the owner know that if there is less than a 50% reduction in lesions or new lesions are still appearing at the time of the recheck, you will perform culture and susceptibility testing before choosing another antibiotic empirically. If you elected to start topical therapy alone first, at the recheck visit you may elect to continue topical therapy if the infection is improving or start oral antibiotic if not improving.

Table 1: International Society for Companion Animal Infectious Diseases guidelines for systemic antimicrobial therapy* for canine superficial bacterial folliculitis (1)

| Category | When Used | Suggested Antimicrobial Drugs | Dosing |

| First tier | Empirical therapy of known or suspected superficial bacterial folliculitis | First-generation cephalosporins (e.g., cephalexin, cefadroxil) | 15−30 mg/kg PO twice daily |

| Amoxicillin-clavulanate | 12.5-25 mg/kg PO two to three times daily (higher doses might be more effective for skin infections) | ||

| Clindamycin | 5.5−10 mg/kg PO twice daily | ||

| Lincomycin | 15−25 mg/kg PO twice daily | ||

| Trimethoprim-sulfa | 15−30 mg/kg PO twice daily | ||

| Ormetoprim-sulfa | 55 mg/kg on day 1, then 27.5 mg/kg PO once daily | ||

| First or second tier | Cefovecin | 8 mg/kg SQ once every 2 weeks | |

| Cefpodoxime | 5−10 mg/kg PO once daily | ||

| Second Tier | First-tier systemic antimicrobial drug and topical therapy ineffective. Selection based on C&S testing | Doxycycline | 5 mg/kg PO twice daily; or 10 mg/kg once daily |

| Minocycline | 10 mg/kg PO twice daily | ||

| Chloramphenicol | 40−50 mg/kg PO three times daily | ||

| Fluoroquinolones: | 5−20 mg/kg once daily | ||

| enrofloxacin | 2.75−5.5 mg/kg PO once daily | ||

| marbofloxacin | |||

| orbifloxacin | 7.5 mg/kg PO once daily | ||

| ciprofloxacin | 25 mg/kg PO once daily | ||

| pradofloxacin | 3 mg/kg PO once daily | ||

| Aminoglycosides | |||

| gentamicin |

9−14 mg/kg IV, IM, or SQ once daily

|

||

| amikacin | 15−30 mg/kg IV, IM, or SQ once daily | ||

| Third tier | Vancomycin, teicoplanin, and linezolid | Use strongly discouraged-reserved for serious MRSA infections in humans | |

| * Therapy must be administered for at least three weeks or until seven days beyond resolution of lesions. Use of the agents listed should take account of restrictions on their use, drug interactions, and safety for the patient. |

Table 2: Systemic antibiotics NOT recommended as empiric choice for Staphylococcal pyodermas

| Antibiotic | Comments |

| Penicillins, ampicillin, amoxicillin | All ß-lactam antibiotics |

| Tetracyclines (doxycycline) | Rarely effective for Staphylococcal pyodermas |

| Streptomycin | Rarely effective for Staphylococcal pyodermas |

Keeping all of these considerations in mind, you choose to begin antibiotic therapy for Junior with oral cephalexin at 22−30 mg/kg twice daily and topical Chlorhexiderm shampoo (4% chlorhexidine). You send home enough antibiotic to cover Junior to his recheck appointment (scheduled for three weeks from now) plus one week. You advise Joyce not to delay the recheck appointment, in order to avoid an unnecessarily long course of antibiotics.

Clinical Response to Treatment

Junior’s owner (Joyce) had to cancel his recheck appointment and could not come back until four weeks after the original appointment. At this recheck you notice minimal improvement in Junior’s skin lesions even though he is still getting the antibiotic twice a day, every day, as recommended. Joyce reports the pruritus is still present and she now remembers that Junior had taken cephalexin before (a couple different times) for similar skin bumps, but only for two weeks at a time. The skin lesions always improved but Joyce’s kids reminded her that the bumps never completely resolved. Had you known this history at the initial appointment, you would have recommended culture and susceptibility testing at that time, to ensure appropriate antibiotic treatment this time around.

|

|

Culture and Susceptibility Testing

When you explain to Joyce that you are concerned about resistant bacteria she becomes very concerned. She explains that her aunt recently had a horrible skin infection that would not respond to antibiotic therapy, and she thinks it was a staph infection. She asks if Junior could have the same infection and if he could give it to her kids.

You try to calm Joyce down by explaining what you know about staphylococcal skin infections. Just as Staphylococcus pseudintermedius is a common inhabitant of healthy dog skin and mucosa but can cause canine pyoderma, Staphylococcus aureus is a common inhabitant of healthy human skin and mucosa but can also cause infections. However, you explain to Joyce that while you cannot say for sure, her aunt most likely had an S. aureus infection whereas Junior most likely has an S. pseudintermedius infection. You also explain that it has been reported that S. pseudintermedius can occasionally be transmitted from dogs to humans, and although S. aureus is primarily found in people, animals can also become colonized or infected by this bacterium. You tell Joyce that the culture and susceptibility test will tell you what type of Staphylococcus species is causing Junior’s pyoderma and what antibiotic will best treat it. You stress that in the meantime, the family can avoid transfer of bacteria/bacterial infection by practicing good hygiene with frequent hand washing (especially those in close contact with Junior) and by giving and applying prescribed medications as directed.

Joyce agrees to the culture and susceptibility test, so you repeat cytology, which confirms a bacterial infection and inflammation. You rupture a pustule on Junior’s belly with a 25-gauge needle, collect the small amount of pus with a swab (see previous sidebar – 05a), and submit it for culture and susceptibility. Before Joyce and Junior leave your clinic, you provide Joyce with an informational handout about the common antibiotic resistant staph infection seen in people (Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus or MRSA) and how to help protect people who have pets with MRSA—Links Below.

More Information:

- General Information about MRSA in the Community

- For more information about pet owners visit University of Minnesota Center for Animal Health and Food Safety

Sensitivity Results and Summary

Four days later you receive Junior’s culture and susceptibility (C&S) results.

Test Results: Numerous mixed flora indigenous to this site; Scant staphylococcus aureus-methicillin resistant

Susceptibility Results:

| S. aureus-me | S. aureus-me | |

|---|---|---|

| Drug | Result | Interp. |

| Ampicillin | R | Resistant |

| Clavamox | R | Resistant |

| Cephalothin | R | Resistant |

| Chloramphen | S | Susceptible |

| Gentamicin | S | Susceptible |

| Marbofloxacin | R | Resistant |

| Oxacillin | R | Resistant |

| Penicillin | R | Resistant |

| SXT | S | Susceptible |

| Tetracycline | R | Resistant |

| Erythromycin | R | Resistant |

| Clindamycin | S | Susceptible |

When you receive Junior’s culture and susceptibility (C&S) results, you are a little surprised but not shocked. MRSA seems to be recognized more and more in animals (as well as in humans). You are glad that you sent home the MRSA information sheet with Junior’s owner at his last appointment and hope that they have been following the guidelines it contains. You realize that you will have to spend more time discussing this situation with Joyce in order to dispel possible fears she may have due to her aunt’s recent infection.

You plan to discuss MRSA with Joyce when you next speak to her, and you do a little research to refresh your knowledge about MRSA. You find that Staphylococcus aureus infections, including MRSA, include superficial skin and ear infections as well as more serious infections such as surgical wound infections, bloodstream infections, pneumonia, osteomyelitis and endocarditis. Established risk factors for MRSA infections in humans include current or recent hospitalization or surgery, residence in a long-term care facility, dialysis, and indwelling percutaneous medical devices and catheters. Symptomatic and asymptomatic MRSA in pet animals has also been documented, so you realize that you need to educate your client about potential risks, precautions, and hand hygiene. You plan to reiterate the prevention points in the MRSA handout to Joyce when you call her and emphasize the importance of continued follow up appointments. Before you call Joyce, however, you must decide what antibiotic therapy you want to use to treat Junior’s resistant pyoderma.

Based on the C&S results, what antibiotic do you want to start Junior on? Select an appropriate answer for each antibiotic listed.

|

|

Lessons Learned When Treating a Bacterial Skin Infection:

- Bacteria may be resistant—you should consider performing culture and susceptibility testing sooner rather than later.

- You need to choose the appropriate antibiotic and use the correct dose regimen.

- You should treat for the appropriate period of time and recheck (sooner rather than later).

- Client communication and education is crucial to obtain compliance and treatment success.

- The symptoms may be ongoing if the underlying causes are not identified and pursued.

Module Summary

- Several diseases or disorders predispose dogs to the development of superficial pyoderma, via different mechanisms.

- Appropriate diagnostic tests should be conducted to rule out these underlying conditions.

- While empirical selection of antibiotics is appropriate and effective in some cases, some antibiotics should not be used empirically, and culture and sensitivity testing is indicated in other cases.

- Clear and comprehensive client education is very important in the successful treatment of canine superficial pyoderma.

Written by: Jamie Umber DVM, MPH, Sheila Torres DVM, PhD, and Jeff Bender DVM, MS

Reviewed by: Sandra Koch, DVM, MS, DACVD

References

1. Hillier, A, DH Lloyd, JS Weese, et al. 2014. Guidelines for the diagnosis and antimicrobial therapy of canine superficial bacterial folliculitis (Antimicrobial Guidelines Working Group of the International Society for Companion Animal Infectious Diseases). Veterinary Dermatology. 25(3):163.